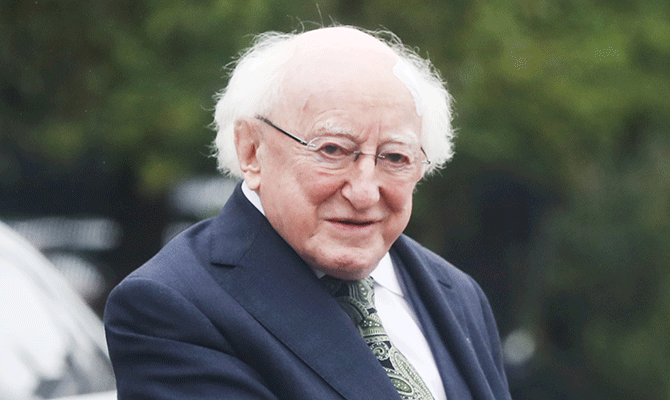

Michael D Higgins has faced accusations of over-stepping his role following comments he has made on a range of topics during his presidency.

In recent years supporters of the state of Israel in the US, UK, Germany and France have attempted to conflate criticism of its ruling ideology, Zionism, with anti-Semitism. They use anti-racism to justify a racist message. After Hamas launched its October 7 attack, Israel supporters believed Israel’s defence forces could use the death of hundreds of its citizens to turn the Gaza Strip and thousands of its Palestinian citizens to rubble without consequence. When European Union president Ursula von der Leyen, in typically German fashion and no sense of historical irony, came straight out of the blocks to give a green light for a Gaza blitzkrieg, it stuck in the craw of Irish President, Michael D Higgins.

She was “not speaking for Ireland” and was sanctioning violations of international law, he said, while opposing also the killing of Israeli citizens by Hamas. Higgins demonstrated sympathy for defenceless Palestinian victims, who would inevitably pay the price of Israel’s vengeance even more so than they had suffered over many decades. His remarks relied also on Irish sentiment in support of the underdog.

To the chagrin of those wishing to see the state line up with western interests, the President, now in his final term, blocked the way.

NEUTRALITY AND DE VALERA

Michael D performed a similar task when Tánaiste Micheál Martin concocted his anti-neutrality forum, which turned into a damp squib. Taking advantage of popular opposition to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Martin, with the Irish Times in tow, thought he could bulldoze the state’s neutrality with hand-picked anti-neutrality ‘experts’.

The fumbling Fianna Fáil leader forgot that neutrality was set in place by the founder of his own party, former taoiseach and president Eamon de Valera, in the 1930s. That was after the League of Nations, forerunner of the UN, failed to oppose in arms the Italian invasion of Abyssinia. World War II neutrality was a consequence. De Valera reasoned that the big powers pursued their own, not the collective, interest. Was he wrong?

This year Martin appeared to think so and did not invite the commander in chief of the Irish Defence Forces, President Higgins, to open his militarised forum.

Higgins’s forum foray, from the outside, remarked that the chair of Martin’s Consultative Forum on International Security Policy, Professor Louise Richardson, had “a very large letter DBE”. She was a Dame of the British Empire. He explained later that he was referring to bold typefaces on conference literature, with which the DBE was advertised. Higgins sometimes smiles as he explains away comments. It shows he thinks he is being clever. In this case, he was.

CONOR CRUISE O’BRIEN

As with his remarks on Israel, Higgins appears to have mastered de Valera’s trick of looking into his own heart to see what Irish people are thinking – although in Higgins’s case, it is his head he mostly relies upon. His is a long political gestation, honed in a party moving to the right as he remained left. The way things are going, he may at some point be all that is left in that party, Labour.

Career wise, Michael D Higgins is one of the luckier members of the Irish Labour Party – and its most principled. He also forms a triumvirate of Irish presidents – Mary Robinson, Mary McAleese, and Higgins himself – whose path to victory is paved over the reputation of another Labour Party member, the late Conor Cruise O’Brien.

Each president in turn opposed, was the victim of, or dismantled O’Brien’s lasting ministerial achievement, the censorship and subduing of RTÉ under Section 31 of the Broadcasting Act during the 1970s.

In 1974 O’Brien referred to Robinson as a “confused liberal” for opposing northern interment, southern non-jury courts and broadcasting censorship. Belfast-born McAleese, working in RTÉ in the early 1980s, fell foul of O’Brien supporters avidly censoring news of hunger-striking republican prisoners in the H Blocks. Twenty years after O’Brien accused Robinson of confusion, the Cruiser opposed Higgins when the latter sank Section 31 censorship in January 1994. That was eight months before the IRA ceasefire.

LABOUR’S DECLINE

Higgins represents a trend that is in retreat in the diminishing Irish Labour Party since the northern conflict erupted in 1968. Its erosion is one reason for Labour’s decline and for the rise in Sinn Féin. Higgins is from the party’s James Connolly tradition, named after the Irish Citizen Army leader who led his troops into the GPO in 1916. Labour’s drift to the right and towards rarefied sections of the middle-class intelligentsia was accompanied by its flight from its republican tradition and working-class roots. It bought into liberalising and modernising Irish society as a substitute for achieving a more socialist transformation. Capitalism was no longer the enemy, the paper-tiger of Catholicism substituted. The north was portrayed with fault lines exacerbated by ‘Catholic nationalism’. Britain’s role in fomenting sectarian strife by elevating a Protestant ascendancy in Ireland, as a means of divide-and-rule, was minimised into non-existence.

Higgins’s alienation from that trend is sometimes buried within complex sociological arguments and renditions of his own poetry. He is from sturdy political stock. Higgins’s father and two brothers served in the IRA during the War of Independence, while an aunt served in Cumann na mBan. Taking the anti-Treaty side, Higgins Snr was refused employment after the Civil War.

Privations, exacerbated by family separation, gave Michael D Higgins a degree of working-class, small-farmer and anti-clerical grit that Labour’s lifestyle socialists lacked. Starting off, like Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald, in Fianna Fáil, he also saw the error of his ways and latched on to the left-wing Noel Browne and Labour.

Peter Casey was one of the challengers in 2018 when Michael D Higgins ran for a second term in the Áras, which the latter won hands down. Casey faced calls to pull out of the race when he claimed that Travellers should not be recognised as an ethnic minority.

‘MICHAEL D’ EMERGES

Higgins’s pathway to electoral success in the 1970s had an indifferent start. It had to contend with church attacks and anti-abortion Fianna Fáil opportunists in the early 1980s. Success in 1987 in Galway West was cemented after Higgins stopped observing that Irish progress was stalled by Irish stupidity. This common enough fault line, picked up from Noel Browne and shared in middle-class circles, gave 1970s and early 1980s Higgins a petulant appearance.

He was successfully advised that popularly mistaken ideas are often the product of ignorance, usually combined with bitter experience. Politicians who thought they knew better had the task of sympathetic education and leadership, not sarcastic put-downs of those less fortunate in life. Higgins thus removed artificial barriers he had erected between himself and the great unwashed. ‘Michael D’, as he became popularly known, was born and he has bathed in electoral success ever since.

Higgins maintained his left-wing persona as colleagues retreated into identity politics. He was unlikely to indulge the jaw-dropping observation of then Labour leader Eamon Gilmore that the 2015 equal-marriage referendum represented “the civil rights issue of this generation”. Abortion, which electorally tripped up Michael D Higgins in Galway West in 1983, remained constitutionally prohibited and negated the bodily autonomy of half the population, whether or not they wished to exercise it. Gay rights did not trump women’s rights.

Higgins’s 1990s parliamentary career was cemented when he was appointment as Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht in 1993, in a unique Fianna Fáil-Labour coalition. He had opposed Labour’s appendage role as partner with Fine Gael in previous administrations. On this occasion Labour had an unusually large contingent of TDs and looked set to hold its own.

Higgins’s was a Cinderella ministry, that inaugurated Teilifís na Gaeilge (TG4) and legislation on funding home-grown Irish filmmaking.

ENDS CENSORSHIP

Higgins’s stated opposition to broadcasting censorship was tested after previous minister Máire Geoghegan-Quinn renewed it in January 1993, prior to Higgins taking office. He then had a year to get rid of it.

To remind him, large posters appeared on Dublin billboards that contained the new minister’s name on an old NUJ anti-Section 31 petition. The poster was emblazoned with the slogan – in larger letters than those advertising Louis Richardson’s DBE – “We’re waiting…” Higgins vented his annoyance at the NUJ, which had nothing to do with this brainchild of the Repeal Section 31 Campaign.

Higgins’s task was aided by Sinn Féin member Larry O’Toole’s victory against RTÉ self-censorship in the High and Supreme Courts in 1992 and 1993. RTÉ had embarked on a confused policy of hyper responsibility, demonstrating that even if censorship was lifted, it would proceed much as if nothing had changed. When Higgins ended censorship in January 1994, that is precisely what a cowed RTÉ did, occasioning increasing embarrassment and ridicule from irritated interviewers and presenters.

That was not Higgins’s problem. He was part of an administration that inaugurated the peace process and the 1994 IRA cessation. He did not reflect his Labour colleagues’ anti-republican baggage, resenting the emergence of Sinn Féin into electoral politics. Higgins had a good sojourn in office and escaped hostility accompanying the somewhat-engineered crises that toppled that coalition from power.

PRESIDENCY BECKONS

Michael D Higgins set his sights on the presidency as early as 2004, after Mary McAleese’s first term. A runoff between her and Higgins would have been of interest but this prospect was shafted by Labour’s hierarchy and Higgins had to wait until 2011. He defeated a very disappointed over-reaching Labour insider, Fergus Finlay, for Labour’s nomination. Finlay, letting his resentments show, was disappointed again seven years later when Michael D decided to run a second time, overturning an impression that he was a one-term Áras occupant.

In the 2011 electoral free-for-all Michael D was blessed by Fianna Fáil’s post-crash meltdown, causing a loss of nerve and no official candidate. Fine Gael’s Nato-supporting Gay Mitchell ran an anonymous campaign. Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness took all the media and establishment heat, while David Norris, Dana and Mary Davis were also-rans.

The battle was on between Michael D and faux Fianna Fáil candidate, the self-styled entrepreneurial guru Seán Gallagher. Higgins cruised past Gallagher just as the latter imploded during a televised-debate interaction with McGuinness. Gallagher’s 2018 reprise was a disaster, with his right-of-centre spoiler role usurped by Peter Casey, and Higgins romped home.

Michael D Higgins has pushed the parameters of the presidency. Following on from Mary Robinson, he has hit the popular pulse, with pronouncements on housing, poverty and structured inequalities in Irish society. Establishment supporters vent their frustration in newspaper columns. They cannot call on popular hostility to presidential pronouncements that does not exist.

Higgins’s long-held convictions with regard to the dangers of western interventions in other parts of the globe and in support of Irish neutrality are generally popular. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael long for the halcyon days when, with a President politically asleep in the Park, they could snore soundly. As Michael D has two years to go, more tossing and turning beckons.