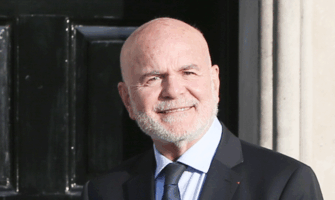

Commissioner Drew Harris

THE appointment of PSNI deputy chief constable Drew Harris, as the new garda commissioner drew mildly critical comment from Sinn Féin but it is key sections of the gardaí that could prove to be Harris’s real problem. Polite noises from garda representative bodies barely disguise the shock and even hostility that the core of the gardaí – the security and intelligence officers in the crime and security branch – really feel about their new boss.

Muffled noises from the newly moderate Sinn Féin on the appointment of a man described as the PSNI’s chief link man with Britain’s MI5 were quickly snuffed out with a welter of positive commentary from the media and mainly anonymous senior gardaí. Interestingly, the Garda Representative Association (GRA) and the Association of Garda Sergeants and Inspectors (AGSI) issued studied statements of polite praise. The GRA made it clear that its welcome for the new boss depended on him securing “all the financial support” needed to beef up, equip and modernise the force while AGSI hoped Harris would be receptive to its members’ “issues and concerns”. These are trade union statements, but the smouldering resentment of the crime and security branch has not been reported on by the security correspondents or anyone else. And more recent private mutterings from GRA and AGSI members indicate some regret at their organisations’ hasty approval statements.

‘A BIT OF A SHOCK’

Significantly, it was not Mary Lou McDonald but retired garda HQ officer, ex-chief supt John O’Brien, who felt free to tell RTÉ – precisely because he is retired and not beholden to senior management – what many special branch members thought of the appointment.

“A bit of a shock,” said O’Brien who argued that no country he was aware of would have an officer directly connected with a security service of another state running its security service. O’Brien was referring not only to Harris’s CV as a RUC and senior PSNI officer but to his particular role as assistant chief constable, “a role in which he worked closely with MI5”, as the unionist Belfast Telegraph put it recently.

For pointing out a basic intelligence tenet O’Brien was roughed up by another Harris, Sunday Independent columnist, Eoghan (no family relation), for his “sour … dirge of negativity”. However, and unusually, Eoghan Harris did not in his attack on O’Brien brag about his occasionally prescient remarks as in September last year when he suggested that if a non-garda officer was to get the top job it should be the “widely respected” Drew Harris. This remark was in the context of Eoghan’s discussion with a retired senior PSNI officer who, even more interestingly, was at pains to dismiss the notion that the sensitive security aspect – as opposed to policing – of the commissioner’s remit should be hived off.

Just how long has Drew Andrews’s recruitment been in the pipeline and under discussion in British and Northern security circles?

O’Brien may not have spelled it out but special branch and intelligence gardaí know full well that western security agencies co-operate with each other; they collaborate with one another and they exchange (up to a point) information. But they also compete with and infiltrate each other – it’s what they do – especially the big boys and they don’t come much bigger than MI5.

As O’Brien pointed out, none of this is a personal reflection on Harris or his professional competence; it’s just that normal state security agencies do not hand over control of their security apparatus to someone so closely connected to another state security machine.

Justice Minister Charlie Flanagan was across the appointment – he appointed the justice department’s ex-secretary general, Joe Brosnan, to the selection panel – as was Leo Varadkar, and government general secretary Martin Fraser was also a panel member. Policing Authority members Josephine Feehily and Bob Collins were on it too. Intriguingly, no serving or past Irish security or even police officer was placed on the panel which nevertheless contained two senior British police officers. These were interim chief constable of the Scottish police Iain Livingstone, and former chief constable, Hampshire Constabulary, Alex Marshall, who is ex-chief executive of the College of Policing UK (as well as general manager of the International Cricket Council’s anti-corruption unit).

CONNECTIONS

Joe Brosnan knows a lot about British spooks having worked with some of those connected to that world when he was a member of the Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC) set up to appease unionist politicians who did not believe the IRA had fully decommissioned arms. In 2006 the IMC cavilled with General de Chastelain’s Independent International Commission of Decommissioning (IICD) which, relying partly on the advice of the then garda commissioner and deputy commissioner, had reported that all IRA arms had been decommissioned.

Alongside Brosnan on the IMC were former Alliance Party leader Lord Alderdice and two senior British security officers, John Grieve and Dick Kerr. Grieve was former director of intelligence at Scotland Yard, a job he stepped into after serving as head of the London special branch and British National Security Coordinator, a liaison post with MI5.

He is a long-time friend of former RUC Special Branch boss Ronnie Flanagan, former chief constable of the RUC. Dick Kerr is a former CIA officer and as deputy head of the CIA was the Washington link with the British Security Service (MI5). In the 1980s, Brosnan was the Irish government’s security liaison man with the RUC and MI5 when government officials were ensconced in the Anglo-Irish secretariat in Maryfield.

It is not known if Brosnan supported Harris’s appointment but given his experience he would surely have been in a position to warn of the tentacles of MI5 and its over arching seniority over UK police forces. If so, other panel members appear to have been unimpressed with any such arguments. But then, amazingly, there were no Irish police or security officers on the panel.

Special branch members have particular concerns about the evidence Harris gave to the Smithwick Tribunal into the alleged collaboration of Dundalk gardaí in the IRA ambush that killed two senior RUC officers in 1989. Smithwick effectively rejected evidence from British agent ‘Peter Keeley’ on a named garda officer in Dundalk Garda Station but received late evidence from Harris that referred to one or more unnamed gardaí as culpable. His evidence said that one unnamed garda had not only tipped off the IRA about Breen and Buchanan’s movements but had also provided information to the IRA on alleged local garda informer Tom Oliver. When asked if his intelligence identified the garda/IRA collaborator, Harris declined to say.

TRIBUNAL EVIDENCE

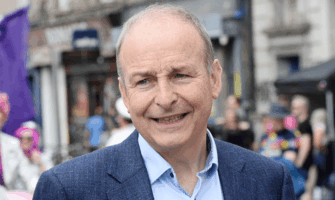

Mary Lou McDonald

The Harris evidence effectively replaced Keeley’s (which had identified one particular garda as an IRA collaborator) leaving Smithwick to conclude that Harris’s unnamed garda had instead supplied the evidence that led to the IRA’s double killing. If Smithwick had identified one or more gardaí as IRA collaborators this would have been bad enough. But concluding that an unnamed officer was responsible has, Dundalk gardaí feel, left a large question mark over all gardaí in Dundalk Garda Station.

Senior counsel representing garda management described Harris’s evidence as “nonsense on stilts”. Another question arising from his input is whether or not he is now in a position to explain in greater detail the intel he partially and coyly referred to before Smithwick. This concerns the murder of Oliver as well as Breen and Buchanan.

The overall legacy of Harris’s tribunal evidence is a simmering resentment among retired Dundalk gardaí who regard themselves as having been at the forefront of the battle against the IRA during The Troubles and over whom there remains a serious question mark. As well, there is a more widespread distrust of Harris, however unfairly, among the Special Branch of a man referred to by Smithwick as “responsible for interface between the PSNI and the Security Service” (MI5).

Over the next five years Harris will have to wend his way through a gauntlet of organisations – GRA, AGSI, Garda Ombudsman, the Policing Authority, Oireachtas committees and so on – all the while vulnerable to resentful Irish securocrats who know a thing or two about dirty tricks. And those who know Harris say the stern no-nonsense police officer has little time for politicians, journalists and bureaucrats.

The other question mark over Harris is his role in the PSNI (good) that has replaced the RUC (bad) and despite media and government references to his sterling efforts in this police reformation there are those in the North who question such praise.

One of these is the Relatives for Justice (RFJ) group that campaigns on behalf of victims – from both sides of the divide – of state violence and collusion as well as any other incidents. There is a plethora of delayed inquests – some going back decades – into killings, which has seen the PSNI offer a variety of excuses for not revealing information to assist such inquests.

This has been a bone of contention between the DUP and SF in the Assembly and contributed in no small part to the breakdown of that body. New legislation proposed in Dublin to allow gardaí to co-operate with these inquests may provide interesting comparisons with past inquests in the North.

In December 2014 the RFJ accused Harris specifically of placing “endless obstructions to officers of the court (at inquests) who are seeking to implement Article 2 rights (of the European Convention on Human Rights protecting the right to life) of their clients”.

Harris has come under criticism as the PSNI front man for investigating collusion legacy cases – that is illegal collusion between loyalist death squads and the security forces in the North. In 2010, and writing on behalf of the PSNI’s Historical Enquiries Team (HET), Harris wrote to the legal representatives of collusion victims to state there would be no overarching inquiries into legacy murder investigations. In other words, each case would be looked at in isolation from any pattern of collusion.

The letter was found to be in breach of Article 2 of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) statutes which assert, inter alia, that the rights of a deceased person are violated if the state fails to put in place “an adequate and effective investigation to protect the right to life”.

Following ECHR rulings on cases relating to collusion in the early 2000s, the UK government undertook to put a two-pronged legacy strategy in place that would look at individual cases and then cross reference them in a “joining the dots” investigation to establish any possible collusive pattern between the State and loyalist gangs.

In particular, this referred to the notorious Glenanne gang that carried out a range of bombings in Dublin and Monaghan and the Miami Showband attack as well as many murders in the North. So it was that the HET was set up in 2005 and pledged to carry out its investigations in a way that “commanded the confidence of the wider community”.

LETTER TO VICTIMS

Peter Smithwick

However last year, referring to the ECHR’s Article 2, the High Court in Belfast ruled that Harris’s letter to collusion victims in 2010 rejecting an overarching investigation of systematic collusion was found to be an “abuse of power” and that “the unfairness here is extreme”. In addition it found that it was in contravention of investigation procedures agreed by the UK government with the Committee of Ministers (CM), a sub-committee of the European Council of Ministers. The ruling stated: “… the structure and process now in place lacks most, if not all, of the essential safeguards which the UK Government agreed with the CM to put in place for future investigations of cases of this nature in order to comply with the decision of the ECHR …”.

An embarrassing dialogue emerged at one inquest when the presiding judge ordered that minutes of a meeting of the Northern Ireland Retired Police Officers Association (NIRPOA) addressed by Harris be revealed. Harris and other senior PSNI officers had been trying to reassure NIRPOA members that they were not being scapegoated by historical inquiries and inquests – NIRPOA had dismissed such inquests as show trials of the RUC and British Army.

At one such meeting with NIRPOA, the then deputy chief constable Judith Gillespie (now on the Policing Authority) told the former RUC officers, “the PSNI is determined to play our part in the defence of the RUC”. The then assistant chief constable, Harris said: “We don’t disassociate ourselves from what happened in the past. I have great pride in my RUC service.”

Bob Collins, a member of the interview panel in Harris’s appointment as commissioner, was chief commissioner of the Equality Commissioner for Northern Ireland and would surely be aware of the ongoing legal spats between victims’ relatives and Harris at coroners’ inquests down the years.

SF and Mary Lou’s rather timid bleating about Harris has been dismissed as down to his decision to not merely question Gerry Adams about Jean McConville’s 1972 abduction and murder but dramatically arrest him in 2014. This is to deliberately miss the point. Harris has been presented as the man to ensure garda reform.

How does this square with the avalanche of criticism from Northern campaigners on his role in allegedly obstructing evidence at delayed inquests into many murders allegedly involving RUC officers?