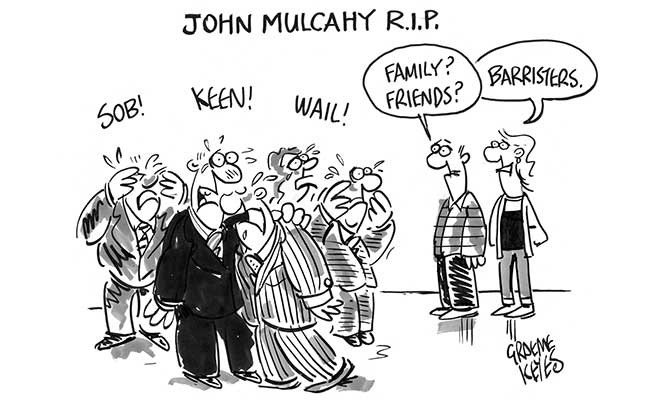

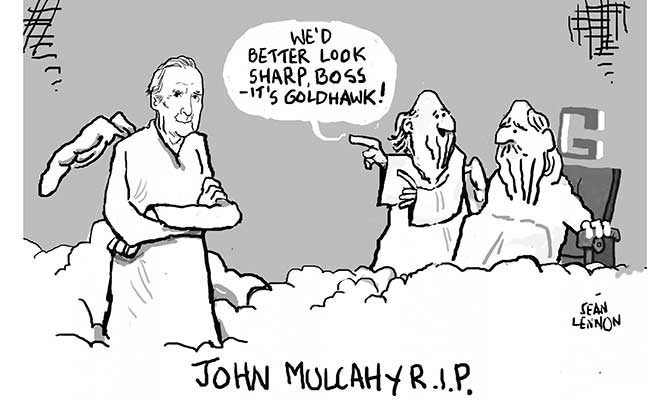

John Mulcahy

A JOURNALIST FOR ALL SEASONS

JOHN MULCAHY will be remembered as not alone the publisher and inspiration behind The Phoenix – as well as the Irish Arts Review, the Sunday Tribune and Hibernia magazine – but as the gatekeeper of Irish investigative journalism. He trained, stimulated and influenced more than one generation of Irish journalists, many of whom went on to succeed in ‘mainstream’ media. His legacy, built up over more than half a century in publishing, exists despite his rejection of the cult of the by-line as embraced by other media ‘personalities’. For John, the work, the story, the uncovering of reality in politics, business and other power centres, was primary – delivered usually in a mocking style designed to puncture the self-important egos in public life.

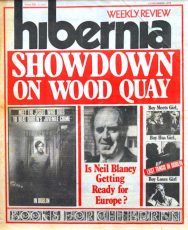

Clichés about the departed can be wearisome, but John’s impact can be measured against the publishing reality in Ireland in the second half of the last century. In the January 1968 edition of Hibernia it was announced that John Mulcahy was taking over responsibility for the publication from the then editor and publisher Basil Clancy. Alongside this statement were Hibernia’s media awards, including the category of “most controversial publication”, under which an implicit statement of intent – anonymous, but undoubtedly from the young Mulcahy – read, “No award. The lack of courage and easy acceptance of ‘authority’, which is so much a part of the Irish scene, is unfortunately reflected in all too many journals.”

Hibernia had been for some years an unusual magazine, guided by its Catholic editor, Clancy (he went on to become Irish editor of The Tablet), and was what passed for a relatively free-thinking, Catholic avant-garde medium in the post-Vatican II period. A year before John took over, its January 1967 edition was dominated by a large spread on Irish education, penned by such as Fr Paul Andrews SJ; St Patrick’s College, Maynooth, lecturer Bro S V Ó Súilleabháin; and secretary to the Church of Ireland board of education, Kenneth Milne. Another lengthy political treatise by Fine Gael luminary Alexis FitzGerald concluded with the view, “I salute Garret FitzGerald as the outstanding Irishman of his generation… His complete integrity, simple patriotism, tireless industry, generosity of heart and mind make his and Fine Gael’s enemies look petty”, and more besides.

The Mulcahy method and editorial outlook was rather different, although elements of a liberal, Catholic outlook were not jettisoned altogether or immediately. But as the north exploded in the late ’60s and ’70s, and as debate intensified across the political spectrum in the Republic, Hibernia became a must-read magazine for an Irish political class, radicals and an intelligentsia not then totally obsessed with property values or the stock market.

At the same time, one of Hibernia’s ground-breaking innovations was the development of business and finance analysis, which hardly existed in the main newspapers or RTÉ in that period. Hibernia also expanded coverage of the arts, books, theatre and film. A young journalist called Maeve Binchy supplied travel articles; another young female writer, Nuala O’Faolain, contributed literary criticism; and Brendan Kennelly wrote about poetry. Seamus Heaney was a regular reviewer as were Francis Stuart, Tony Cronin, John Banville and Claud Cockburn.

INQUISITIVE

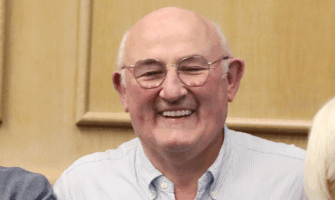

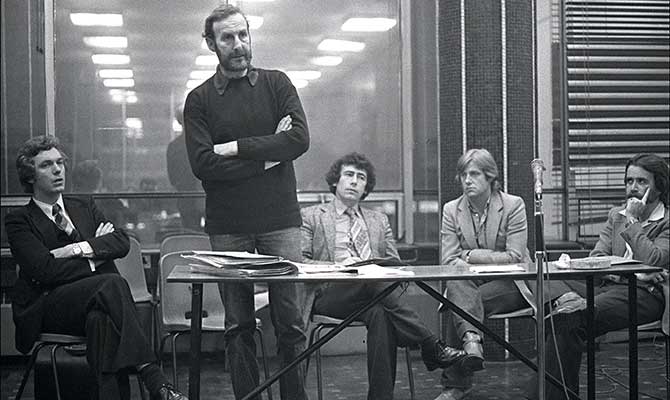

John speaking at a prisoners’ rights meeting with former TD and retired judge Pat McCartan (left)

and former minister Joe Costello (right), 1980.

At the heart of Hibernia’s editorial output, however, was the inquisitive scrutiny of current affairs, in particular its northern coverage and planning scandals in the Republic at a time when nobody went near this latter, murky world. A chap called Ray Burke, then a Dublin county councillor, came under special scrutiny for his dual role as an estate agency representing developers while dealing with planning matters as a local representative.

Much of this may seem unremarkable today, but the rich Hibernia diet was being proffered in the publishing desert of the ’60s and ’70s when Irish journalism was a staid, conservative beast. Hibernia under John Mulcahy and his wife, Nuala (as literary editor), provided not merely a radical and refreshing alternative to the conservative media, it opened the door for others.

Critical and challenging writers at the Irish Times and other publications followed, many becoming household names (even ex-Sunday Independent editor Anne Harris wrote fiery, radical columns in Hibernia).

It is testament to John Mulcahy’s almost cussed determination to ply his trade, rather than boost or market his by-line, that he was indifferent to the sometimes self-regarding and self-generated publicity bestowed on other media personalities.

The demise of Hibernia in 1980 came with a raft of libel cases from such as Bishop Philbin, a priest, a judge and a special branch man in an apt catalogue of the type of authority figures that Hibernia rutted up against. If he had never dipped into publishing again, John could legitimately claim to have broken the media mould with Hibernia alone.

Undeterred, John immediately drew in publisher Hugh McLaughlin for his next project. Together they launched the Sunday Tribune in 1980 with John as editor.

The Tribune became a launch pad for another group of Irish journalists, including Geraldine Kennedy, appointed by John as the country’s first female political correspondent and who subsequently became the first female editor of the Irish Times, and a voluble Eamon Dunphy, who was granted his first regular soap box at the Tribune. Mary Holland, a personal friend and long-time colleague also wrote for the Tribune, as did Tom McGurk.

However, McLaughlin was the long-time publisher of an eclectic group of titles, ranging from Business and Finance to the Sunday World, and the inevitable culture clash saw John exit the newspaper after less than a year – although not before he had laid the foundations of the newspaper.

After restless reflection, the next Mulcahy venture materialised in early 1983, deliberately titled The Phoenix. This time John was determined not to become compromised by partnership with a publishing magnate or the exigencies of the mass media market. He reverted to the Hibernia method, under a new format and with a sharper focus on chancers in high places. John’s eldest son, Nick Mulcahy, was indispensable to the launch of the magazine before departing to the Sunday Business Post and then to his own magazine, Business Plus.

Nick was replaced as deputy editor in 1990 by Paul Farrell, a classic product of the Mulcahy academy. Paul (ex-Irish Tatler group) would acknowledge that under John’s tutelage he grew from orthodox, young business journalist into the ‘engine room’ of The Phoenix.

REVELATIONS

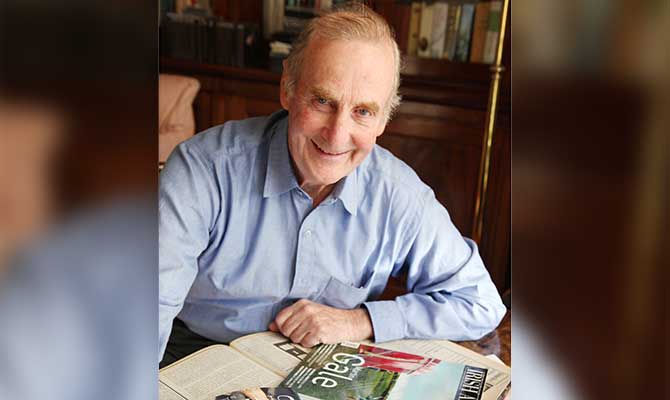

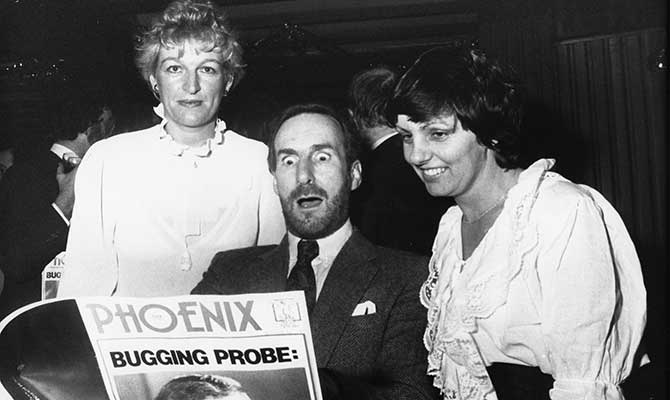

At the launch party of The Phoenix in 1983, John with long-time trusted colleague Noreen Russell (right) and Pat Moylan (left)

While much has since emerged about Charles J Haughey – ‘Squire Hockey’ as John dubbed him – no more searching article about the origins of Haughey’s wealth has been written than John’s investigation into the former taoiseach in the first Phoenix edition in January 1983. It was 14 years later before a direct hit was landed on the Squire, when Goldhawk broke the news that Haughey had received over IR£1m from ‘the Big Fella’ while he was taoiseach (see The Phoenix, 4/12/96).

This was one of the most sensational (as opposed to sensationalist) stories The Phoenix broke.

Another early story came in a special investigation into Dermot Desmond and Michael Smurfit’s involvement in the Telecom/Ballsbridge site, which resulted in The Phoenix being published with blank pages (see edition 4/10/91) as Smurfit Web Press refused to print it. However, Labour leader Dick Spring read the entire article into the Dáil record and when John Glackin produced his report on the affair it confirmed Goldhawk’s findings.

Another Phoenix special was the revelation – following an angry outburst by Flood Tribunal chairman Judge Alan Mahon against Liam Lawlor over Lawlor’s dealings with the Revenue – that Mahon himself was forced to settle with the Revenue to the tune of IR£20,000 (IR£16,000 in under-paid tax and IR£4,000 in penalties) some years earlier (see The Phoenix, 10/10/2003).

Goldhawk also revealed the hardly gratuitous pension arrangements at Irish Nationwide, where boss man Michael ‘Fingers’ Fingleton received a e27.6m pension payment (see edition 27/6/08).

The revelation about the love child of moral custodian Fr Michael Cleary (see The Phoenix, 14/1/94) led to frantic efforts from some surprising media quarters to undermine the story.

More recent stories have focused on the position and remuneration of Angela Kerins at Rehab; a campaign against the efforts of gardaí to charge Ian Bailey for the murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier (see edition 20/4/18 and passim) stretching back eight years to a time when the entire media had Bailey tried and convicted.

In 2015, John’s ‘Save Our Rubens’ campaign – to stop assorted masterpieces from the Beit Foundation art collection being sold off to the highest bidder at a London auction house, to where they had been secretly shipped – proved influential. As a result, a number of the most valuable paintings remain in the state today.

CONFRONTATIONS

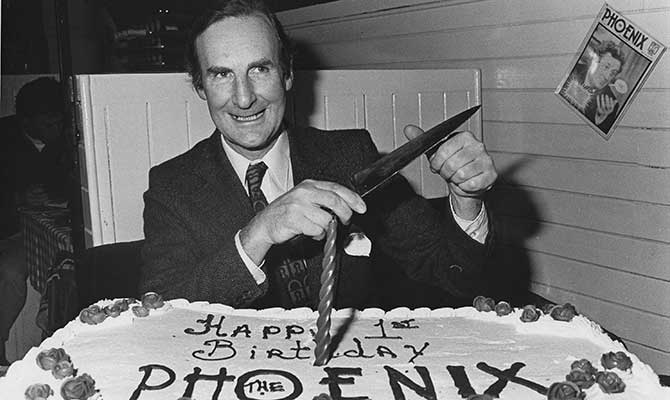

Sharpening his ‘pen’

Some of these stories provoked a serious backlash, with the Bailey coverage resulting in the magazine being found guilty of contempt of court (see edition 29/7/16).

Other stories resulted in visits to the Four Goldmines, where efforts to bring Goldhawk to book were sometimes successful, sometimes not. Avril Doyle, then MEP, cost The Phoenix a six-figure sum in costs and damages in 1995. Less successful was an effort by Irish Times journalists to have Goldhawk incarcerated, via a High Court action for criminal libel in 1990, for setting the political record straight about their late colleague, the Reverend Stephen Hilliard. A subsequent effort to have Goldhawk censored by the NUJ Ethics Council was also unsuccessful.

A more dangerous adversary was convicted drugster John Carway. He retaliated against Goldhawk’s unfavourable coverage by firstly arranging for a sachet of heroin to be planted in The Phoenix office and then arranging for IR£100,000 in counterfeit notes to be planted in the Mulcahy family residence (see edition 16/6/89 and passim).

Perhaps the quintessential example of Goldhawk’s ongoing tussles with the rich and powerful came with a review of Anglo Irish Bank’s performance, concluding with the verdict that the bank was “technically bankrupt” (see The Phoenix, 12/12/08). As the first copies of The Phoenix hit the streets in central Dublin that Wednesday evening, a solicitor from MOPS acting on behalf of Anglo rang to demand that all copies of the mag be withdrawn – on pain of a High Court application that evening to injunct The Phoenix from appearing. Following a game of high-stakes legal poker that lasted until midnight, Anglo blinked – the bankers realised that we knew the score about their finances. There was no application for an injunction and no copies of the magazine were withdrawn.

Goldhawk’s brief, Robert Dore, who has battled for this publication for over 30 years, was at the table when Anglo tried to execute this litigious bluff.

These and other confrontations with the good, the great and the ugly have been occasional hazards at this publication, as well as the odium and disapproval of many decision makers in the media, whose resentment at being scrutinised is often greater than any politician.

Earlier, a brief foray in 1987 into the UK market with the magazine Digger proved a bridge too far for John, who at that stage was running The Phoenix and writing his novel, Union.

That novel, a lively account of events surrounding the 1798 rebellion, the Act of Union, 1800 and Robert Emmet’s rising in 1803, was also a penetrating analysis of class, religion and nationality in those seminal years.

INFLUENTIAL

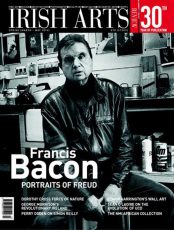

‘Prolific’ is hardly an adequate description of John’s publishing output and his revamp of the Irish Arts Review was one of his most accomplished achievements. When he took over as editor of the Irish Arts Review in 2002 the publication was in the form of an annual yearbook with a small circulation. Its base was essentially the art trade plus the then relatively small pool of art historians.

Under John’s editorship things changed radically. While he was careful to preserve the heft and weight of good scholarly articles, he hugely broadened the magazine’s readership – changing the publication to a quarterly with a greatly increased page size – to such an extent that it overtook the circulation of the UK frontrunner Modern Painters.

He also broadened the IAR’s baseline, developing a large corporate sector and, newspaper man to the core that he was, extending its appeal far beyond the narrow confines of fuddy-duddy art historians. He regularly stimulated debate and among his many chosen targets were the underdevelopment of NCAD, those 1916 commemoration projects, Ireland’s obsession with tourism, Tony O’Reilly’s art collection, the Beit Foundation, the role of the National Gallery, board vacancies on the national cultural institutions and so on.

Add to this the major development of its online presence and the digitalisation of the title’s entire archive and it will be seen that John has a just claim to having been the most influential man in Irish art circles for nearly 20 years.

He was also responsible for ensuring that the visual quality of the magazine was unmatched and far better than that of Modern Painters or any equivalent magazine. The reproduction of images on its large-format, chalk-surfaced paper meant that Irish artists, for the first time, had a truly splendid visual magazine, capable of rivalling the splendours of a publisher like Skira. Crucially, John also extended the magazine’s baseline into the contemporary realm, with each issue featuring a detailed interview with a living artist. Today, the IAR is the flagship and, indeed, the only major Irish arts magazine.

THE MAN

Venceremos!

John’s editorial inspiration was partly scientific and partly human. His method was that of constant scepticism, contempt even, for the endless cant from self-important public figures. A perpetual spirit of inquiry, supplemented by a self-imposed distance from the bubble, helped him to retain this mood. (He declined, for example, an inviting offer to break bread with Dermot Desmond some years ago).

His comprehensive knowledge of politics, business and the arts, leavened by a sense of humour, imposed a quality control and editorial standard on those of us who worked with him.

Most of all, he maintained an infectious enthusiasm for the story. Be it about a political party leadership heave or a local golf club, his journalists were made to feel his intense focus and interest in whatever angle they were pursuing. And while the collective Goldhawk writes in a laconic, laid back and disrespectful tone, the overriding imperative was the supply of new information for readers.

John Mulcahy, the man, the intellectual, aesthete and ideologue, defied easy characterisation, but his circle of friends and interests go some way to explaining him. He would have described himself as a constitutional Republican and he retained a distaste for the revisionism and self-loathing of the modernist establishment. Despite his relatively privileged background – Clongowes and a family background that included many doctors – his Australian birth, working experience in Canada and mobility resulted in his felt experience as an outsider, detached from what came to be known as Dublin 4.

In a rare political outing, he became the driving force behind a petition against internment in the early ’70s, collecting over 100,000 signatures, which he personally delivered to 10 Downing Street. And motivated more by media freedom than politics, John railed against Section 31 for the two decades and more that the odious legislation was in force.

At the same time, one of his earliest and most enduring friendships was with Fine Gael thinker John Kelly. Another FG friend was Garret FitzGerald, although a heated argument over the north during dinner in a Greek restaurant resulted in ‘Sir Garret’ becoming a favourite epithet in The Phoenix.

Following the 1983 story about Haughey’s wealth, John was summoned to the Berkeley Court hotel for lunch with the man himself. He was hardly a close friend of the Squire, but they did share a cynical sense of the world and John admired Haughey’s early positions on the national question. After a pleasing repast, the mood darkened as Haughey leaned over and inquired, “How can you write such shite about me in The Phoenix?” After a few seconds of discomposure, John collected himself and shot back, “You should be down on your knees for what we DON’T write about you”, in a barely veiled reference to Charlie’s dangereuse liaison with gossip columnist Terry Keane.

And despite PJ Mara’s distinct edginess about Goldhawk’s coverage of his boss, the two enjoyed a long-time friendship, again, mostly because they had a mutual sense of humour.

ADVOCATE

In-depth editorial discussion with editor Paddy Prendiville

Politically, John’s Republicanism was supplemented by a strong attachment to an independent Irish foreign policy and in particular Irish neutrality, as illustrated by relentless and continuing coverage in The Phoenix. And his commitment to the desperate plight of Palestinians has also been a constant.

Through Hibernia in particular, he also revealed a concern for the oppressive poverty in Ireland as well as support for those campaigning to relieve it.

There are many in the world of music and the arts generally who also regarded John with affection – some more grudging than others given the unsparing coverage in the magazine. Where John’s knowledge of the arts, business and government came together was during his time on the board of the National Gallery. He joined the board at the time of Lochlainn Quinn’s chairmanship and was on the board with the Knight of Glin and über philanthropist Loretta Brennan Glucksman. Unfazed by these luminaries, John displayed his trademark independence and dedicated himself to ensuring the governance and marketing of the National Gallery was fit for purpose and that its redevelopment and autonomy would be maintained. He spent time studying tourism and retail trends and helped shape investment at the gallery to ensure its offering was right for the markets it serves. The larger shop, the outreaching to bus tourism and other measures were all advocated by John.

At the time of John’s tenure, the arts department had plans to bring many of the national cultural institutions more within its grip, but John resisted this fiercely, serving diligently on the National Gallery board sub committee that saw off the department and any incursion into the gallery’s independence.

John pressed for redevelopment and advocated for Irish artists, especially for Harry Clarke who he felt was not fully acknowledged in Ireland. Never afraid to be alone on an issue, he was resolute in fighting to protect the gallery for generations to come and to never allow it to be compromised by the dead hand of a Government department.

John Mulcahy was uneasy with ingratiating sentimentality and his editorial offices were always and primarily a place of work. He would likely not want it said in public that, on occasion, he showed significant acts of kindness to his staff and colleagues. But he did, as this writer and others know well. What we also know is that we were fortunate to have worked for an inspirational journalist and publisher who changed the face of Irish journalism. That he retained an unquenchable sense of mischief throughout was a perk of the job.

Paddy Prendiville